“Are you able to keep your chest rotated left during the entire motion? You will know you are on the right track when you feel muscles along your inner left thigh and left abs working.” Evan, a new client, replied, “What do you mean? I’m doing the rows.” I said, “Do four more reps, and try to keep your chest rotated left even when you lower the weight.” Evan completed the four reps as if he didn’t hear a word I said… possibly moving even faster through the exercise. He then looked at me for approval. I smiled and said, “Awesome. On the next set we will lift the front of your foot with this little plate and have you reach with your right arm.” Evan completed three reps of the exercise – he kept a better position -and his eyes grew bigger. Baffled, Evan said, “That was much harder! I felt my inner thigh and abs a lot! This didn’t feel like the last set at all… how the hell did those little changes do that?!”

Evan is a former collegiate basketball player, and he has spent many hours training hard in the weight room. Like the vast majority, he focused on moving more weight and ways to add more intensity to try to pack on some muscle, sprint faster, and jump higher. He admits he was in chronic pain at the time. After college he kept many of the training habits he was taught, although he concedes he doesn’t train his legs often because every time he tries he aggravates his back or his knees. Furthermore, despite not playing basketball nearly as much as he used to he still constantly feels stiff and restricted. Evan is 32 years old, but he will tell you he feels much older. We started working together to clarify his goals, and recapture the athletic qualities and healthy movement he needs to live an active life.

You Can Have It All – To A Certain Degree

When we perform an exercise we have to keep the purpose in mind. Most people just want to burn calories, try to “tone” their bodies, or be “stronger”. There is nothing wrong with that per se; however, these are ambiguous terms that result in people literally just focusing on density of the work performed – applying greater force for a given distance or duration: I ran five miles in 30 minutes, I was the fastest to complete 300 burpees, or I benched 275 pounds three times. Again, THERE IS NOTHING WRONG WITH THESE TYPES OF FITNESS GOALS… unless the changes we make to our body to achieve these goals sacrifices or diminishes some other characteristic of athletic performance or health we need.

For instance, some of Evan’s training history involved continually training to sprint faster. To progressively improve speed his body changed, the best it could, to more efficiently push his body weight forward. Basically, Newton’s third law of a reaction to the action of force pushing into the ground behind him. To be more resourceful, his muscles and skeleton will bias toward:

- A position of forward lean to be able to push the ground away behind him.

- Joint positions with as little motion or flexibility as possible to efficiently apply force into the ground (“strength” isn’t wasted on control of large ranges of motion when it is needed to push into the ground).

Evan still would need to be able to perform some form of running mechanics so motion will need to occur somewhere. Watch a few people sprint, including Evan, and it is obvious individual movement restrictions alter how this will look to some degree. The different displays of running show the individual’s strategies to create a forward lean, tighten muscles, and limit joint motion to apply as much force into the ground as possible.

Living Beings Always Move Toward Efficiency

Nature always does things in in the most efficient way possible. Human physical changes are about creating efficiency to handle a repeated stressor. In a scenario of Evan exercising to run faster, he is regularly stressing his body to apply greater force into the ground to propel forward faster. His body then creates new physical norms to regularly respond to this stressor in an effective and timely manner.

This is like a thermostat in a house. Say it is a steamy 100 degrees Fahrenheit summer day. A HVAC system manages a 68 degree room temperature when the system is on throughout the day much differently than the strategy used if they system was off and turned on only after you no longer wanted to make everything you touch a damp sponge. The HVAC system would need to work much harder if it were off and needed to close the gap from 100 degrees to 68 degrees. Furthermore, repeatedly letting the room temperature rise to 100 degrees before the HVAC kicks in to adjust the temperature back to 68 degrees would be incredibly inefficient. When the HVAC system is constantly on, small adjustments are needed to respond to the changes in temperature throughout the day. The minor tunings create apt responses to keep a specific outcome – a 68 degree room.

Fitness training is meant to program the human “thermostat” to effectively respond to a change in stress. A repeated stressor will calibrate an individual to be able to make small physical adjustments to handle variations of the stressor; thus a relatively quick and useful response. However, turning the entire stress response “off” and not being at the ready for predicted reoccurring high pressure events would be terribly inefficient. In fact, it would be life threatening in some scenarios. No physical changes would be made, and if the same stressful task were repeated it would never become easier to manage. The odds of a successful outcome would decrease because we would see no change or improvement in ability.

Efficient In What Context?

Now, just because specific traits are efficient in one task, doesn’t mean they are ideal for handling the demands of another. Physical adaptations are not useful for every context. The common extreme used to explain this is the difference between a 100 meter sprinter and a marathon runner. Obviously they have different conditioning and force production needs, and following a twelve week running program for a marathon runner wouldn’t improve a 100 meter sprinter’s performance and vice versa.

However, the sprinter and the marathon runner are trying to produce a maximum relative force; the work is just over different durations. Thus, when we dig a little deeper we find similar physical adaptations to efficiently run straight ahead. So, each of these individuals are still biasing their skeletons and muscles into positions to efficiently produce force – think arched lower backs, and “tight” calves, quads, and hamstrings. The extreme archetype of each will have different body types and muscle mass, but they both create physical change to limit their ability to rotate and decelerate their bodies. They bias the structure of their bodies to run more efficiently forward in a straight line.

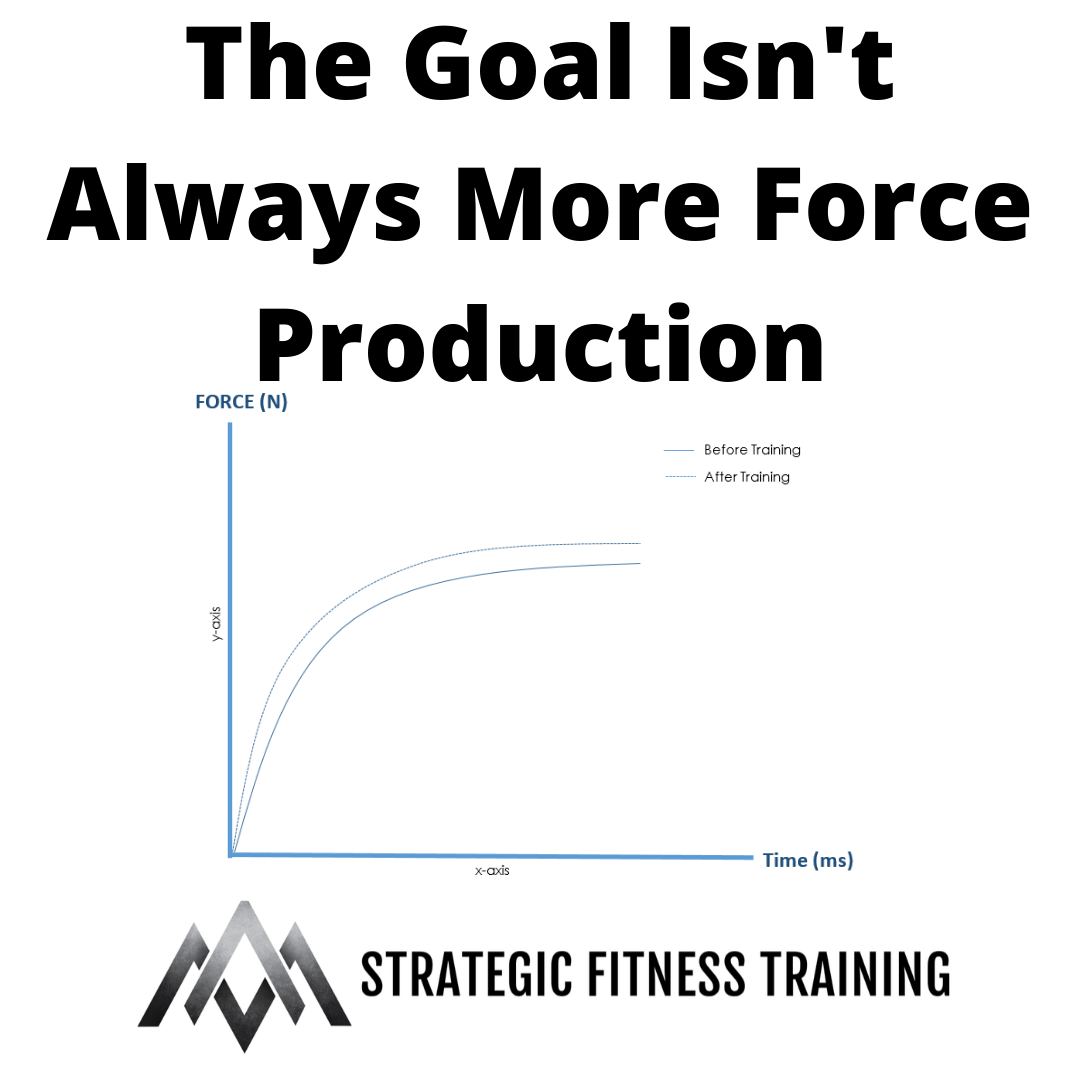

The skeletal and muscular adaptations – I am not referring to muscle mass – that occur to become a faster runner, repeatedly moving a maximum weight in the gym, or performing body weight activities to failure are not commonly appreciated. Consequently, these structural changes are overlooked when planning an individual’s training needs. The physical gains from attempting to sustain or increase production of force during specific activities are not necessarily useful for other activities that require force absorption – decelerating the body (like brakes on a car), changing direction, rotating, or even resting to let the body recovery.

Becoming really efficient at producing force into the ground is similar to the HVAC system working really well at keeping the living room a cool 68 degrees, but it sucks at cooling the bedroom. Trying to get some sleep in a 100 degree bedroom while you are paying for the HVAC to make the living room so comfortable would be at minimum frustrating, and still lighten your wallet when the monthly electric bill arrives.

Many people, like Evan, who bias the majority of their fitness training toward sprinting faster, maximizing weight on an exercise, or constantly working to failure will probably have some pain and frustration. Especially when people with restricted movement repeatedly attempt to perform tasks requiring greater synchronized joint range of motion at high speeds, like rapid deceleration or explosive rotation. They have traded the cool, comfortable air in the bedroom to try and maximize and steady the temperature in the living room.

Typical fitness training involves an individual improving his ability to produce force in a certain manner, but despite performing different exercises he is constantly using the same force producing strategies. This person keeps focusing on the HVAC of the living room and not the rest of the house. Moreover, this person can become so efficient at producing force that he is essentially at the ready to do so even when it’s not needed – his human thermostat is adjusted. This individual may be trying to relax or sleep, but his body is still primed to be in the gym.

Hard Work Is Still Required

Training to try to achieve full range of motion, force absorption, change of direction, rotation, and rest would sacrifice some degree of max force output. Exercise execution to recapture full movement at the joints requires a higher level of detail. The need to control large joint excursions is inefficient and leads to the decrease in max strength. However, this does not mean you are not working hard. You are still in the gym moving and lifting weights. Likening the performance of an exercise with subtleties to regain movement to the same exercise without the particulars is like comparing apples to oranges. The anecdote of Evan’s experience performing one arm dumbbell rows is an example of the nuance.

Once again, physical adaptations to produce maximum force are not bad. Many athletes and fitness enthusiasts need them to be competitive or participate in the activities they love. The challenge is to help these individuals determine to what degree of the physical changes for maximum strength is required, and help them develop some gradation of the movement strategies necessary for force absorption, change of direction, rotation, and rest. There will always be some reciprocal trade-off. The question for every fitness activity always becomes, “how strong is strong enough?” relative to the context of an individual’s needs.