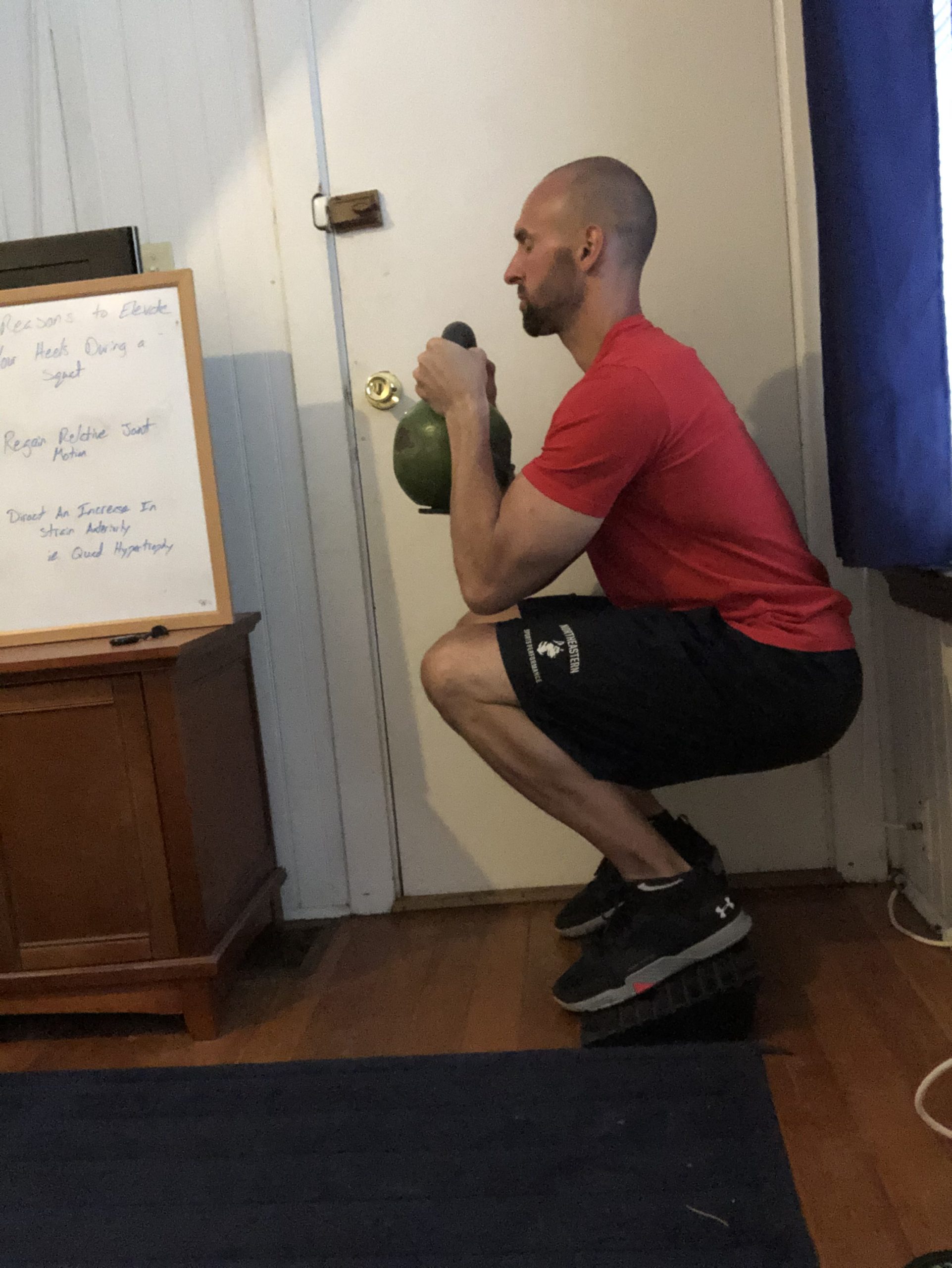

I administered one of our regular re-assessments with a client the other day. Her name is Rachel and she is a Division I soccer player. After the assessment I informed her that she would not need to elevate her heels on a slant board when performing goblet squats in the day’s training session. She looked at me sort of perplexed. She then stated that although she feels she can squat much lower than before, she still feels restricted as she attempts to lower to a desired depth. Rachel asked, “I still need help keeping my body weight back toward my heels, right?” Those type of questions always make a coach feel special; she obviously had been paying attention during a conversation a few weeks ago. “Pushing your weight back is currently our goal. However, we must constantly monitor how much force we want you to produce and your access to specific ranges of joint motion. The ‘tightness’ of some off the muscles on the back side of your body changed. So we are going to try a different strategy.”

Squats and Gravity

Our definition of a squat is to sit straight down on top of your heels with very little forward lean of your upper body – sitting back, as in reaching for a chair and leaning forward, creates more of a hip hinge exercise and is not true squatting. Sitting straight down on top of the heels is very challenging for most because we must constantly resist gravity. This is an incessant force smooshing us to the ground, and we must produce force to stand and move against it. The battle against gravity is amplified when an individual is taller, adds weight – body fat or with resistance training, or is creating explosive athletic movements to leave the ground.

There are two overarching strategies humans can use to resist gravity:

- We can inhale and expand like a balloon to maintain shape.

- We can squeeze the contents/fluid of our body with muscles to pressurize and maintain shape.

We need to be able to use each strategy rather equally to maintain full range of motion in joints throughout our body. However, since we are constantly attempting to overcome high relative forces, especially with exercise, we tend to bias the body’s strategies to create muscle compression that is popularly referred to as “tightness.”

The muscle tightness impacting the ability to display a beautiful squat is primarily on the back side of the body from the base of the skull down to, and including, your glutes. Think about how all these muscles would be working to keep you standing, prevent you from falling to the ground, or trying to overcome gravity to walk, climb, run and jump. So, these muscles aren’t going to easily yield to allow us to descend our hips to the ground if they are so well trained to constantly fight and overcome gravity. This is the case even when we are trying to consciously do so.

Mobile or Constrained Bone Segments

To better understand how the muscle tightness along of the backside of the body impacts squatting we can use the analogy of a stack of twenty-five stones to represent the all the bones of the pelvis and spine. There is motion at each level the stones touch, and the accumulative motion would make it a highly mobile structure. Now picture balancing the stack of stones in the palm of your hand as you begin to walk. You would need to make constant micro calibrations with your arm as you moved so the stones would not topple over.

Now, let’s imagine if the same stack of stones did not have motion at each level because they were glued together one on top of the other. This would make a rigid structure that could support greater external load; we could apply some compressive downward force without the stack buckling. However, if this structure was balancing in the palm of your hand when you walked, the arm would actually make much larger movements to attempt to prevent the structure from toppling over. The constraint of the glue to make one solid object consolidates and directs all the required motion to the segment with movement capabilities.

Next, imagine instead of walking with a stacks of stones in the palm of our hand we attempt to move the hand up and down from chest height to hip height. Similar calibrations with your arm would be needed to maintain balance of the stack of stones. The the unglued version would descend in a more vertical line, but requires many small adjustments to do so. Lowering this stack without toppling it would be challenging at higher velocities. Whereas the arm holding the twenty-five glued stones would have much larger horizontal movements to prevent it from falling over. It would also be able to descend quicker but at the expense of larger calibrations.

Real Squats = Motion in Spine

Like the stack of unconstrained stones, our spine has to be able to move, and allow constant micro calibrations to occur to drop our hips straight down on top of your heels. If our spine is “glued” then larger horizontal motion would be needed in an area like the hips to maintain balance. This could be seen as pushing our ass backward and leaning forward, as in reaching for a chair. Large horizontal hip displacement is more of a hinge then a squat. (Note: There are other compensatory motions besides the hips moving backward, but this is an easy example to see.)

The degree to how much of the pelvis and spine are “glued” with muscle tightness will dictate how much the hips must go backward versus down. Furthermore, there may only be muscle tightness in specific areas of the pelvis and spine – some areas can move while another can be glued. This would impact the depth of the squat.

Why We Elevated Rachel’s Heels

This brings us back to Rachel no longer needing to elevate her heels to goblet squat. When she first began training with us, her pelvis and spine was mostly restricted (aka “glued”). We emphasized releasing that muscle tightness along the entire posterior side of her body with all of the exercises in her program. Orientating her body into specific positions would target muscle tightness at certain segments of the pelvis and spine. For example, heels elevated during a goblet squat would help with the area between her shoulder blades and around where the spine and pelvis join. As she progressed, some muscle tightness dissipated and she regained movement in these specific areas which allowed her to move through new ranges of motion.

Elevating Rachel’s heels would not have been useful strategy to regain range of motion if she didn’t have tightness in between her shoulder blades and at the upper posterior pelvis regions. Some people may push their hips horizontally immediately when attempting to squat, but it is due to a different area of tightness – below the shoulder blades and at the bottom of the glutes. Elevating their heels may make their squat look good. However, the heel elevation could just be helping them hide the muscle tightness. Continual assessments are important when working to recapture movement capabilities so we aren’t fooled by these types of scenarios.

Furthermore, we could use the strategy of elevating heels to focus strain to the anterior legs, i.e. the quads. This would promote more quad strength and/or growth. However, this doesn’t mean we are necessarily releasing the tightness we discussed between the shoulder blades or at the pelvis and spine junction. Eventually, increasing the amount of external weight, or the way we hold the external weight, will decrease movement in the spine and pelvis to increase the strain on the quads. This is a trade-off we may decide is warranted for an increase in sports performance.

We didn’t want to increase the strain on Rachel’s quads. She has adequate strength and excessive muscle growth wouldn’t help her play soccer. We chose to use a heel elevated strategy while squatting to regain joint range of motion. Then, we gradually decrease the elevation until it is gone to challenge her to maintain the new motion. Weight or velocity are progressively added to the squat motion once she is capable of maintaining the joint range of motion with her heels on the ground.

Conclusion

Athletes like Rachel require a larger degree of freedom at their joints to maximize agility, to handle the unknown forces and positions encountered while playing, and to give their bodies the ability to rest and heal when not competing. The goal is to have someone like Rachel hold onto her movement capabilities as long as possible while increasing the complexity/stress of activity. We use assessments to monitor movement changes. Exercise execution, or selection, is altered if a challenge takes away too much of her joint range of motion. Repeating this process over and over again creates the guidance to track and customize her fitness program.