“We need to improve our conditioning,” said the Coach. “Well, how are we determining that is what we need? Most of the team passed your conditioning test before the season,” I replied. “Well, they don’t stay in shape during the season. They look like they are stuck in mud out there.” “So every day, throughout the whole season, the whole team looked out of shape?” “Yes! Watch Amy… she can’t move! She always gets one of the worst scores on the conditioning test!” “Ok… so we are discussing Amy. Anyone else?” The Coach’s tone of voice increased more as her frustration with my questions grew, “They all can’t move side to side or explode to the rim! Especially Amy!”

At this point, I would decide whether to ask more questions that came off as condescending such as, “So Amy’s abilities represent the team?” or “are we still discussing conditioning?” Another option is explaining how there is no way the student-athletes who play high minutes each game need more conditioning; the Coach’s definition of conditioning is referring to the max intensity thirty to sixty second variety. Also, the student-athletes who don’t play high minutes but complete full practice aren’t “out of shape” because the Coach runs the shit out of them each practice. However, the low minute players may need more time spent in games or game like scenarios in practice – conditioning is context specific.

Furthermore, I can go on and on how recovery and mentality – of both the athlete and Coach – impact the perception of conditioning. However, I’ve learned over many years logic and reason is useless with emotionally charged individuals with different beliefs. Especially with those who feel they are in an authoritative position.

Haphazard High Intensity Exercise

A majority of the collegiate Sport Coaches, and Strength and Conditioning Coaches, I have interacted with love to extrapolate a small sample size – one or two athletes – to represent the team. Thinking in absolutes is easier to comprehend and more comfortable. Besides this being a cop-out to a Coaches’ failures, it also is incredibly unfair to the student-athletes. In fact, there are student-athletes falsely criticized and punished. Every year I’ve been in the collegiate setting, I have had meetings with Sport Coaches annoyed “so and so” is out of shape. The Sport Coaches give this student-athlete, or the whole team, extra high intensity conditioning as a result. Misperception of an individual’s level of conditioning is the most common occurrence, but this discussion can also apply to the perception of strength or power.

In any instance, the course of action in many Coaches minds is always more intensity – otherwise everyone is soft, everything is too easy, and there is no effort. To be clear, I am not saying there are not “lazy” student-athletes with poor conditioning, inadequate strength or power, etc. You can readily find student-athletes that lack the motivation to improve physical characteristics with conditioning or in the weight room; they just want to play their sport and don’t want to do any additional work.

There are many different reasons for lack of effort. Some motives probably even hard for the student-athlete to articulate and for anyone working with them to comprehend. However, everyone involved has to do a better job determining when a lack of perceived physical abilities is indeed work ethic related, and not try to solve every problem with a hammer. The subsequent order consequences of haphazardly piling on more max effort training to an individual or team may be an even greater detriment to performance. More exercise is not always better, especially the involuntary variety.

I briefly mentioned how recovery, and mentality matter. Each is a complex topic adding to the perception of conditioning, strength, and power problem. Both still need to be better understood and managed to make better exercise or conditioning recommendations. However, an imperative topic constantly disregarded in the fitness world is there are different breeds of humans, just like there are different breeds of dogs.

There are Different Breeds of Humans

Intuitively, the different breeds of human is obvious when you look at a crowd of people. There are noticeable differences in shapes and sizes. Going to a popular dog park will show this too. You will see Yorkies, Chihuahuas, Vizslas, Greyhounds, Labs, English Bulldogs, Pit Bulls, St. Bernards, etc – each type of dog originally bred to perform specific jobs. However, the fitness industry promotes an illusion of different people becoming which every shape and size they want with however much of an athletic trait they want. The truth is:

- You can become a bigger or smaller version of the breed of human you are. A St. Bernard can be lean but it will never be a Chihuahua or even a Lab, and vice versa for fat Chihuahuas or Labs.

- You can alter your physical traits to some degree but all breeds have different floors and ceilings of ability. An English Bulldog can have varying degrees of conditioning, but at some point even the best conditioned English Bulldog is just going to stop and sit down if you try to treat it like a Vizsla. Moreover, many breeds may run fast, but not compared to a Greyhound.

- Over pursuit of non-breed like physical traits may require greater sacrifices of health. I talk about the sacrifices of joint range of motion for strength and muscle gain all the time (here and here).

- Different breeds may require different fitness strategies to improve a similar physical quality. I would have to be much more conservative attempting to increase the activity level of an English Bulldog than with the Vizsla.

Humans are bred to excel at specific physical work just like dogs. Some humans are created by mom and dad to favor bouncing, sprinting and change of direction. They make it look effortless. Others can lift really heavy things off the ground easier than most. Some people’s designs are biased to run long distances while others are predisposed to be really hard to move off a spot– obviously not the sexiest job and not going to make the highlight reels, but still can be useful in some context in sports.

There will even be individuals with a combination of multiple traits. This makes them good at a few jobs, but maybe not in the highest percentile in a specific one. Although, the genetic athletic freaks have it all because they just have much higher ceilings, and floors, in their physical abilities. However, there are always reciprocal trade-offs, and we are always discussing how much of each trait rather than absolutes.

How Exercise Impacts Different Breeds

Strength and conditioning adds a level of complexity to genetic gifts each breed of human presents. How impactful it is depends on the type of power, strength, and conditioning exercises performed, and the type of human. Someone born with a body type biased toward long distance running can certainly train to be more explosive or add strength, but they will have a ceiling of ability possibly below the floors of the really bouncy people or the individuals put on this earth to pick things up and put them down. Vice versa for those that can pick up heavy things, but want to run long distances fast.

One breed of a human trying to gain traits of another is fine up to a point. This is usually seen as developing some of our weaknesses. But, we may be squandering or hindering our natural superpowers, and setting some people up for failure, with too much emphasis on improving those perceived weaknesses and/or training all breeds the same way.

A human only has so much time and energy to allocate toward different areas of training; especially, athletes requiring an array of physical qualities and game tactics for sports like basketball or soccer. How much exercise should be focused on physical traits an individual isn’t designed to excel at? Tough to say. But, placing an individual in a position to best utilize his natural gifts is much more efficient and better coaching. Plus, attempting to change one breed into another will have consequences. Different individuals performing the same task have different outcomes. Idiosyncrasies, some based on genetic body type, make results from tasks totally unique. For example, the same activity performed by different people does not mean an equal amount of energy spent or recovery needed. Much like the English Bulldog and Viszla both attempting a two hour walk at the same rate. The cost is much higher for the English Bulldog – and always will be barring health issues.

Furthermore, the most unrecognized mistake is utilizing the training of one breed, which has a bias toward excelling at the given training task(s), and using that same type of training plan for a breed with the opposite bias. Thus, the training plan may be the exact opposite strategy needed and could further promote the weakness that was trying to be developed in the first place.

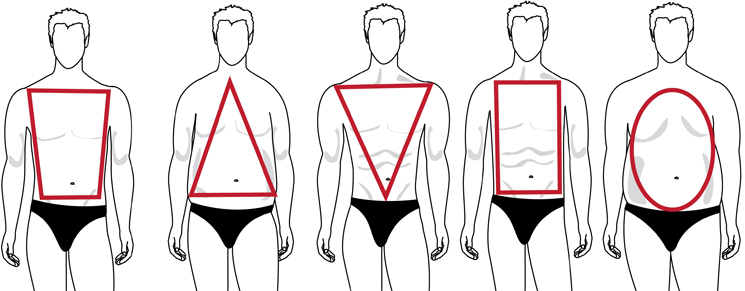

Think the “V” shaped basketball player with broad shoulders and narrow hips versus the pylon shaped basketball player with broader hips and a narrower upper body. Basically, the “V” shaped athlete is physically designed to lift off and bounce, so he will excel at jumping activities. The pylon shaped athlete – possibly a good center in basketball – is designed to plant his feet and be a sturdy, immovable structure. Thus, this individual doesn’t display athletic traits like jumping out of the gym or quickness.

The common thought is that the pylon breed is bad at jumping so he needs stronger legs and more jumping in his training to improve at getting off the ground. In actuality, the pylon individual is bad at jumping because the physics of his body shape is designed to be pushed toward the ground by gravity.

This means an individual biased toward a pylon shape requires more effort to run – it is a greater amount of work to run the same distance compared to other breeds! Also, an initial strategy of holding extra weight with barbells or dumbbells – aka increasing gravity on this person – to increase leg strength may actually make the pylon shaped athlete even more grounded and hinder jumping. The pylon breed is “losing” to gravity so much that early on in the weight room he needs assistance with bands when strengthening his legs to make him lighter. He can transition to adding weight once he demonstrates in increase in velocity of movement with diminishing band assistance.

Different Breeds Require Different Expectations

It’s wrong to have the same expectations of athleticism for one breed that you have for another. Again, seems to be common sense when we look at the shape and sizes of people. It’s pretty easy to pick out who will perform better on some conditioning tests just by looking at the size of folks. However, the shape of bone structure can make it a bit trickier. There can be two individuals who are approximately the same height and weight but have totally different conditioning and force production abilities based on the form of their bodies. Assuming an individual with the body shape biased toward being grounded/stationary/unmovable will develop, or can develop, a similar degree of explosiveness, or conditioning as people whose body shapes are biased toward those traits is absurd.

This is what the Coach was doing with Amy. Amy isn’t a bigger girl like the ones who play center or even power forward. She plays shooting guard, and is approximately the same size as the other guards. However, she has a skeletal structure biased towards being a pylon – she is more grounded and it’s harder to move once she plants her feet. She is a very good shooter, and understands the tactics and fundamentals really well. She can contribute at the Mid Major Division I college basketball level, which is why she gets significant minutes, but has to be utilized based on her strengths.

Amy is a different breed than the quick guards or even the guards who can run all day. This doesn’t mean she isn’t trying to run hard or be explosive. In fact, Amy has battled many lower leg injuries because she attempted to lift and condition with the same exercises, volume, and intensity as the other guards. Her game can’t be the same as the other guards, and nor can her fitness plan.

Conclusion

Your breed dictates which physical jobs you will excel at. Now, I understand there will be outliers for each breed that may make it possible to be superior at a task best suited for another. Or, that the “ideal” breed may be unfit for its job, i.e. a fat Greyhound won’t run as fast. Furthermore, there are many people who aren’t “pure breeds” of a specific shape so they won’t show an obvious bias.

The goal is still attempting to place the right breed in the right job to succeed while allowing it to develop its strengths and some of its “weaknesses.” Everyone involved must know the progress on those weaknesses can’t be compared to the strengths of another breed, and attempting to create an uncharacteristically large improvement of a weak trait will sacrifice greater health or possibly performance to do so. The challenge is objectively determining and tracking performance of strengths and weaknesses, and defining when the pursuit of improvement of any trait has become detrimental. It’s not about treating all breeds equally, but treating them all fairly.